Asking "Why?"

"Why?" The question we grow passionate about as we start developing our sense of self, from the age of 2.

The prelude

Finally, after 12 months, it’s here!

I’ve been waiting for the perfect moment to launch this newsletter. When to start? What to write? Which platform to use? Feeling paralyzed by wanting to choose the best, most scalable solution. Falling into what I call the freedom trap or being a maximizer, as Barry Schwartz says in The Paradox of Choice. And it’s exhausting.

I’ve always struggled with perfectionism—the excuse of procrastination. Originally, I wrote this newsletter draft 1 year ago last January. But as I mentioned before, it wasn’t the right time. It wasn’t the right place. And other priorities took hold.

*insert excuses here*

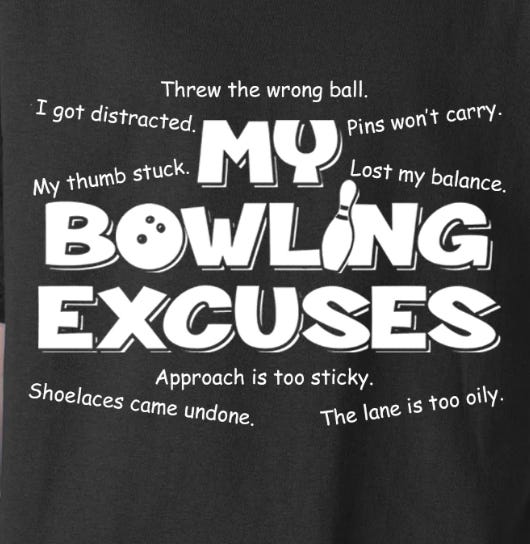

As a kid, I was an extraordinaire of excuses. When I was in a youth bowling league, my mom even bought me a shirt like this.

Today isn’t the perfect moment either, because the perfect moment doesn’t exist. But it’s my attempt at taking imperfect action. Choosing progress over perfection. Practicing non-attachment. Relinquishing control.

Okay, time for the actual programming below.

On asking “Why?”

We ought to ask ourselves why more often. Growing up as kids and teenagers, our favorite question is undoubtedly, “Why?” Erupting a barrage of whys from the age of 2 as we start developing our sense of self.

Why do I have to stop playing with James?

Why do I have to take out the trash?

Why do I have to do my homework?

Why do I have to clean my room?

Why do I have to go to school?

But we don’t ask why? enough, as we age. Maybe it’s because of toxic workplaces that discourage and resent this question. That’s a deep dive for another day though. My point here is that we’d all benefit from asking ourselves, as adults, more of these same why questions.

Today I read an article alleging that remote work is contributing to Gen Z being the loneliest generation. It left me feeling frustrated, overwhelmed, and a deep-seated anxiety.

My initial reaction was to write a long-winded reply . . .

Which I followed through on and did. I nearly wrote an article in response to the article. Because of LinkedIn’s 1,250 character count limit, it took me 3 comments to fully respond.

Over an hour later, after eating leftover spaghetti bolognese for dinner, I was pacing around the kitchen snacking on walnuts asking myself, *hmmm* “Why do I feel this way?”

Why am I feeling anxious?

Why am I feeling frustrated?

Why am I feeling overwhelmed?

Finally, some clarity sprinkled to mind.

Well, the startup company I’m building, Helm, is directly advocating the opposite message of this article. We talk about the future of work being more flexible, remote, and asynchronous, with Gen Z strongly pushing for this. Feelings of loneliness and isolation are an epidemic through the roof, yes, and remote work is a scapegoat to the root causes.

We point to all of these ideas in the context that a better future of living is a world of work that is more flexible, with freedom of choice at the core.

So when the argument is made against this case why was I feeling frustrated? Anxious? And overwhelmed?

Because the point of the article indirectly challenged my identity as a founder of Helm. My identity as a thought leader for the future of work. It challenged the future I set out with intentions of Helm succeeding.

The article challenged Helm’s entire manifesto on the future of work.

Borrowing the lesson of “Yes and . . .” from improv.

This article can challenge my views, which is great for avoiding echo chambers to spark fruitful discussions. And I can feel frustrated with it. And it doesn’t discount me thinking the article’s argument is flawed.

Yes . . .

And it’s still important for me to be aware of why I felt these emotions so viscerally after reading the article.

As you have your next conversation, read the next piece of news, make your next judgment, ask yourself:

What if the opposite were also true?